A Simulation Example:

Unbiased Individuals Often Have Biased Group Discussions

Background.

Important decisions are frequently made by groups rather

than by individuals. This is particularly true in

organizational and governmental settings. The reason

is simple: groups can often bring more information

to bear on a problem, which should allow them to make a

better-informed decision. That groups typically have

more information at their disposal than individuals do is

the result of background differences among the group

members. That is, due to variations in education,

training, day-to-day experiences, and the like, group

members often possess a certain amount of problem-relevant

knowledge that others in the group do not have.

Let's call this uniquely held knowledge “unshared

information.” This stands in contrast to “shared

information,” which is problem-relevant knowledge

that every group member possesses. By pooling their

unshared information, members increase the size of the

knowledge base on which the group as a whole can draw,

which should increase their collective ability to make an

informed choice.

Discussion is the primary means by which groups are presumed to pool their unshared information. That is, as they talk about the problem at hand, it is commonly assumed that members mention the decision-relevant unshared information they hold. The reality, however, is quite different. Groups often do a rather poor job of pooling their unshared information during discussion (for a review of the empirical literature, see Larson & Egan, in press). Instead, their discussions tend to be biased, focusing more on the shared information that everyone in the group already knows, and less on the unshared information that each member knows uniquely. What is remarkable about this bias is that it can arise even when all of the group members are individually unbiased, that is when each is equally willing to discuss both the shared and the unshared information he/she holds. Said differently, even unbiased individuals tend to have biased discussions. [To read an internet blog post that provides a more detailed discussion of this bias and the decision-making errors it can produce, click here.]

A Prototypic Scenario. To get a better sense of what I mean by a biased discussion, consider the following scenario. Imagine that three physicians are tying to determine what is causing a patient 's illness so that they can prescribe an appropriate treatment. Let's assume that there are 24 separate pieces of information bearing on this patient's case that should be taken into consideration when making a diagnosis (e.g., the patient's age and gender might be two such pieces of information). Half of that information (12 pieces) is known to all three physicians. Of the remaining 12 pieces of information, only Physician A is aware of 4 of them, only Physician B is aware of another 4, and only Physician C is aware of the final 4 pieces. Thus, each physician knows 16 of the 24 pieces of case-relevant information: 12 that both of the other two physicians also know (shared information), and 4 that neither of the other two physicians know (unshared information). Now imagine that the three physicians meet in a conference room to pool their information and diagnose the case.

What information will this group discuss and what will they overlook? Research with real physician teams in situations very much like this suggests that their discussion will be biased, and will exhibit three distinct characteristics (cf., Larson, Christensen, Abbott, & Franz, 1996; Larson, Christensen, Franz, & Abbott, 1998):

The simulation assumes that during discussion group members take turns recalling and mentioning case-relevant information, and that they do so one item at a time. But it also assumes that each member is individually unbiased with regard to whether that information is shared or unshared. That is, given two pieces of information that might be recalled and mention during discussion, one shared and one unshared, each member individually is no more likely to mention the shared than the unshared information. Finally, the computer simulates one group discussion, then another, then another, then another, etc., in rapid succession until a very large number of independent discussions have been simulated. It then reports the average results across all of the simulated discussions that have been run.

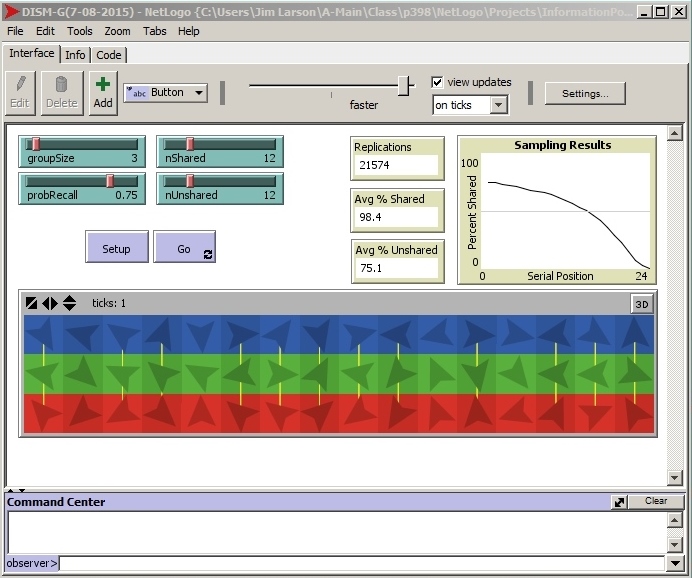

The

video1

demonstrates the model in action (click here or the image

to the right). This particular run of the simulation

used the parameter values described above (i.e., 3-person

groups, 12 pieces of shared information per group, and 12

pieces of unshared information per group, with the

unshared information distributed equally among

members). In addition, a recall parameter was set

such that during discussion members were able to recall

(and so discuss) only 75% the information they actually

knew. Note that in the video the blue, green, and

red color bands at the bottom of the display represent the

three members of each group. Each chevron-shaped

object (called a "turtle" in NetLogo) represents one piece

of information held by one member. Finally, shared

information is distinguished from unshared information by

the yellow lines that connect them (i.e., turtles that are

linked by yellow lines represent shared information, while

turtles that have no links represent unshared

information). During the simulation run in this

video there is a great deal of action going on in this

colored part of the display. Unfortunately, that

action takes place at a very high rate of speed, too high

to be seen easily in the video. (To give you a sense

of just how fast the simulation runs, consider that in

this video more than 21,000 group discussions are

simulated in less than a minute!) In class we will

spend some time talking about this simulation and

exploring how it works, and when we do we will slow it way

down so that you can see every detail of the action that

takes place. By doing this you will come to

understand how unbiased individuals can nevertheless have

biased group discussions!

Things to Notice. The main results of the simulation appear in the four tan-colored boxes in the upper-right portion of the display. There you will see (a) the number of group discussions that were simulated (referred to as replications), (b) the average amount (percent) of shared information that was mentioned during these simulated group discussions, (c) the average amount (percent) of unshared information that was mentioned, and (d) the how often shared (rather than unshared) information was the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, ... 24th piece of information mentioned during the group discussion.

At the end of the video you will see that, despite being composed of members who are individually unbiased, the discussions of these simulated groups nevertheless were very biased, just as the discussions of real groups tend to be. As can be seen in the tan-colored boxes, these simulated groups typically discussed much more of their shared information (nearly all of it) than they did of their unshared information (only 75% of it). They also tended to discuss their shared information before their unshared information. This latter result can be seen in the graph, where in first half of discussion (left side of the graph) the percentage of time that shared (rather than unshared) information was mentioned is well above 50%, whereas in the second half of discussion (right side of the graph) the percentage of time that shared (vs. unshared) information was mentioned is well below 50%. In short, shared information tended to be discussed earlier than unshared information, just as in real groups.

Finally, one thing you cannot see in this video is the effect of the group members' ability to recall their information during discussion. That is because all of the discussions simulated in this video assumed the same recall ability (75%). We would need to run the simulation several times, using different values for the recall parameter, in order to see the effect of recall. This too is something that we will examine in class.

1 This video was made several years ago, and was first used in connection with a version of this course taught in the Department of Psychology (as PSYC 398). The video has been tested with Windows Media Player. It may or may not work with other players.

Discussion is the primary means by which groups are presumed to pool their unshared information. That is, as they talk about the problem at hand, it is commonly assumed that members mention the decision-relevant unshared information they hold. The reality, however, is quite different. Groups often do a rather poor job of pooling their unshared information during discussion (for a review of the empirical literature, see Larson & Egan, in press). Instead, their discussions tend to be biased, focusing more on the shared information that everyone in the group already knows, and less on the unshared information that each member knows uniquely. What is remarkable about this bias is that it can arise even when all of the group members are individually unbiased, that is when each is equally willing to discuss both the shared and the unshared information he/she holds. Said differently, even unbiased individuals tend to have biased discussions. [To read an internet blog post that provides a more detailed discussion of this bias and the decision-making errors it can produce, click here.]

A Prototypic Scenario. To get a better sense of what I mean by a biased discussion, consider the following scenario. Imagine that three physicians are tying to determine what is causing a patient 's illness so that they can prescribe an appropriate treatment. Let's assume that there are 24 separate pieces of information bearing on this patient's case that should be taken into consideration when making a diagnosis (e.g., the patient's age and gender might be two such pieces of information). Half of that information (12 pieces) is known to all three physicians. Of the remaining 12 pieces of information, only Physician A is aware of 4 of them, only Physician B is aware of another 4, and only Physician C is aware of the final 4 pieces. Thus, each physician knows 16 of the 24 pieces of case-relevant information: 12 that both of the other two physicians also know (shared information), and 4 that neither of the other two physicians know (unshared information). Now imagine that the three physicians meet in a conference room to pool their information and diagnose the case.

What information will this group discuss and what will they overlook? Research with real physician teams in situations very much like this suggests that their discussion will be biased, and will exhibit three distinct characteristics (cf., Larson, Christensen, Abbott, & Franz, 1996; Larson, Christensen, Franz, & Abbott, 1998):

- As a group, they will tend to discuss their shared information before they discuss their unshared information (an order effect).

- As a group, they will also tend to discuss more of their shared information than of their unshared information (a quantity effect).

- The size of the above quantity effect will grow larger as the group members' individual ability to recall the case-relevant information decreases (a memory moderator effect).

The simulation assumes that during discussion group members take turns recalling and mentioning case-relevant information, and that they do so one item at a time. But it also assumes that each member is individually unbiased with regard to whether that information is shared or unshared. That is, given two pieces of information that might be recalled and mention during discussion, one shared and one unshared, each member individually is no more likely to mention the shared than the unshared information. Finally, the computer simulates one group discussion, then another, then another, then another, etc., in rapid succession until a very large number of independent discussions have been simulated. It then reports the average results across all of the simulated discussions that have been run.

| |

Click

to View Simulation Video |

|

|

| Works

with Windows Media Player |

Things to Notice. The main results of the simulation appear in the four tan-colored boxes in the upper-right portion of the display. There you will see (a) the number of group discussions that were simulated (referred to as replications), (b) the average amount (percent) of shared information that was mentioned during these simulated group discussions, (c) the average amount (percent) of unshared information that was mentioned, and (d) the how often shared (rather than unshared) information was the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, ... 24th piece of information mentioned during the group discussion.

At the end of the video you will see that, despite being composed of members who are individually unbiased, the discussions of these simulated groups nevertheless were very biased, just as the discussions of real groups tend to be. As can be seen in the tan-colored boxes, these simulated groups typically discussed much more of their shared information (nearly all of it) than they did of their unshared information (only 75% of it). They also tended to discuss their shared information before their unshared information. This latter result can be seen in the graph, where in first half of discussion (left side of the graph) the percentage of time that shared (rather than unshared) information was mentioned is well above 50%, whereas in the second half of discussion (right side of the graph) the percentage of time that shared (vs. unshared) information was mentioned is well below 50%. In short, shared information tended to be discussed earlier than unshared information, just as in real groups.

Finally, one thing you cannot see in this video is the effect of the group members' ability to recall their information during discussion. That is because all of the discussions simulated in this video assumed the same recall ability (75%). We would need to run the simulation several times, using different values for the recall parameter, in order to see the effect of recall. This too is something that we will examine in class.

1 This video was made several years ago, and was first used in connection with a version of this course taught in the Department of Psychology (as PSYC 398). The video has been tested with Windows Media Player. It may or may not work with other players.